Michael: That look at these ordinary things is quite surreal at times, for example, in that song „Mother of a Dog“. The first line is: „I was raised by the son of a mother of a dog“. (I wave my hand to Karl who’s listening to something on his headphones, repeating my remark and the first line of the song.) Is that a fragment of a dream?

Karl Hyde: I was raised by the son of a bitch.

(A moment of silence)

Michael: Ohh. But this was not meant to be autobiographical?

Karl: Barely. The more you find words the more you find ways of painting the same picture. I’m not interested in painting the same picture with the same words. Actually I’m not that interested in writing something that is ugly for the sake of it. There’s a way of making something beautiful out of things intrinsically ugly. At the root it can be quite violent, but there’s a way of finding beauty in it.

Hundemutter (translation: Martina Weber)

Ich wuchs beim Sohn einer Hundemutter auf

Ich wuchs bei einer Hundemutter auf

Ich wuchs bei einem verrückten Schnapper auf

Haar schwarz und Zähne

Kein Reliefdruck

Im Haus des Hundes

Und du durchstößt meine Haut

Skinhead mit Rubbellos

Du denkst du siehst hart aus

Bier und Fleisch und Sonne

Der letzte Zug führt ins Königreich

Nun, ich suche jemanden

Sie ist dunkel, hat einen Pagenschnitt

In der Hand eine französische Nummer der Elle

Na ja

Ich weiß nicht, wer sie ist

Alles, was ich weiß, ist Information

Ich wuchs beim Sohn einer Hundemutter auf

Ich wuchs bei einer Hundemutter auf

Ich wuchs beim Sohn einer Hundemutter auf

Ich wuchs bei einer Hundemutter auf

Michael: This song really seems to be a great example for that. In the intro I’m hearing – for the first time in my life on a record with the name „Eno“ on the sleeve – a short appearance of a harmonica, like in the old blues songs, and then all these scenes – like childhood and teenage memories. And when you think everything comes to an end, with Karl’s tender singing that somehow blows all the harshness away, the listener will be surprised by a beautiful long instrumental passage.

Brian: So it goes of into a different world really. That is a characteristic of a lot of these songs of being both on the Earth and in touch with it, not pretending that you are somewhere else, but also being mentally at another level that you might call a transcendent level, and trying to be both at the same time. I’m sure that’s what all spiritual and religious disciplines have been about, the idea of being in touch but not being trapped by the world.

Michael: The last song of the album, „To Us All“, is so dark when you hear the lyrics: it could be written by a soul mate of Samuel Beckett, there are lines like „From the blood that we just we couldn’t spill / From the ones that we just couldn’t kill / We spin a world in a dizzying fall / To see the things that will happen to us all.“ But the sounds and the melody have an incredibly warm, embracing quality. it sounds like a lullaby for the end of the world, or, to our endlessly numbered days.

Brian: That was actually a much longer song earlier, there were four other verses, and I took them all out. Just left that bit. And the four other verses for me painted the picture too fully. They filled in all the details, and it wasn’t so good then. So I emptied it and was just left with what had actually been the climax. So the song had built up to those two verses that exist. As a sort of climax, but then I thought: get rid of the build-up, just have the climax! I’ve never really done a song in quite that form except it’s slightly like a song of my very first album, called „On Some Faraway Beach“, where there’s a long lead-up, and there are three short verses that sort of just sit there like a little island in the song.

Michael: Yep, I was thinking of your first song album, „Here Come The Warm Jets“ once in a while when listening to „Someday World“, because of that exuberant energy, the sudden changes of mood and atmosphere. You quite often look for a last song that functions as kind of release at the end of an album. Think of the pure melancholia of the last song, the title song of „Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)“, a deep sadness that is sort of balanced by a melody that could go on forever …

Brian: Just talking as a composer, one of the things we were really spending a lot of time thinking about is structure. How can you make things that have unusual and different structures, rather than „here’s the verse, here’s the chorus, here’s another verse, there’s a chorus, then there’s another bit, a middle eight or an instrumental“? We just thought: let’s just start off in general with unusual structures; let’s see what happens. I had this phrase in my head all the time: cities on hills, ‘cause a lot of the cities I like best are built on hills. And so the houses, the buildings have to kind of mould themselves round this complicated geology, and it always seems to create lovely buildings, interesting buildings. So we decided to start off not with a flat plane but with hills. So we just made rules that this is gonna be the structure of the song, we don’t even know what the song is gonna be, but we’re gonna first of all define a structure, and we did it using dice on the table there, anything, just to push us into a place where we were a little bit more lost.

Michael: By the way, both your voices have some fine affinities. On one song, „Who Rings The Bells“, Karl sings with a vulnerability that reminds me a bit of Morrissey’s singing on the verge of vanishing, on the first Smiths album which in fact was the only Smiths album I really liked. With your voices you cover a wide terrain …

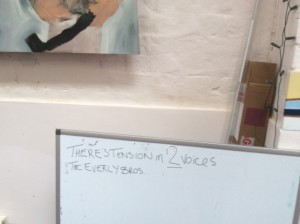

Brian: Our voices really work together very well. That was just a lucky accident. We don’t have the same sound speaking voice at all, but when we sing our voices really come to pretty much the same place. And I think on some of the songs … there’s that song „Witness“ for example, where I’m singing in parallel the whole time, I’m just singing one note, he’s moving in the melody, and I’m just keeping one note all the way through, and I think that’s also an unusual effect: it sort of sounds like my voice is a shadow of his voice. It’s as if his voice is casting a shadow. I’ve never really heard that effect except with our great heroes, the Everly Brothers. We can’t refer it to the Everly Brothers, ‘cause we like the way those two voices are so joined: if you try to sing an Everly Brothers song, you very often find yourself singing one line of Don’s part, and one line of Phil’s part. There isn’t like a lead voice, and a secondary voice. They’re both as interesting.

Part 1/4

Part 3/4

Part 4/4